“Six armed AFP officers, wearing ballistic vests stormed my apartment … I was frisked despite still being in bed”. This was the experience of share-trader Gabriel Bernarde after notifying corporate regulators about an alleged fraud in the financial markets. Michael West reports on the persecution of the powerless.

Gabriel Bernarde’s experience as a whistleblower arose in testimony before the Senate last week. Not only had he been raided at home, in bed, and frisked, but they gagged him too. Good thing the police officers didn’t have to use their battering rams to break down the door to Bernarde’s terrace house in Richmond because his fiancé Emily Pallet was up early on the morning of August 5, 2021 and kindly opened the door for them.

Funny how the police never gagged anybody from PwC for selling state secrets to foreign clients, or frisked the bank chiefs in bed for their systemic banking frauds! Funny how nobody at the Big End of Town ever seems to be raided at home by armed police officers. Ever.

It was the 6th King of Babylon, Hammurabi, back in 1772 BC who declared: “The first duty of government is to protect the powerless from the powerful”.

If you look at the experience of Gabriel Bernarde though, the government seems to think its first duty is to protect the powerful from the powerless. Bernarde is a small time market analyst and ‘short-seller’ who blew the whistle on what he thought were suspicious practices by ASX listed company Tyro Payments. The attacks on the powerless are even more egregious when you consider persecution of Julian Assange, Tax Office whistleblower Richard Boyle and Afghan war crimes whistleblower David McBride, who faces court next week and a possible jail term of 50 years.

Stonkered

This reporter has long catalogued abuses in accounting and law by the Big End of Town. And so it was that we were stonkered last week to hear of a statutory body we had never come across, the Companies Auditors Disciplinary Board (CADB). The primary duty of this exceedingly low-profile government organisation is to prosecute wrongdoing by auditors – you know, the Big 4 types such as PwC, EY, Deloitte and KPMG.

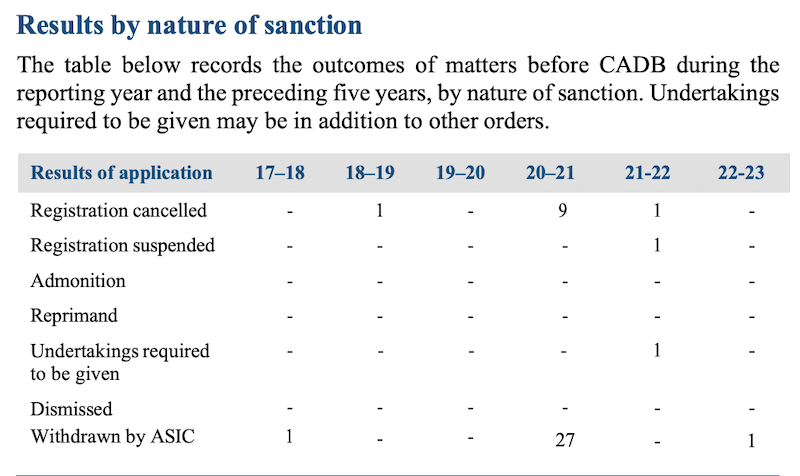

In light of Gabriel Bernarde’s testimony, it was intriguing to hear the testimony of the CADB operatives, if operatives is the operative word because here is their performance over the years.

Yes, you read it right, nothing last year, except one case dismissed and withdrawn by ASIC. Delving back a bit further, we find that the CADB has prosecuted 25 cases since April 2008. That’s a majestic strike rate of 1.5 per year. 2016 to 2018 appear to be the lost years. Oh, and 2010 to 2013 also appear to be the lost years too, when nothing was recorded.

The big – and singular – enforcement action last year was – no, of course not, not KPMG’s massive audit cheating scandal or any of the dozens of Big 4 audit scams exposed over the years in these pages – rather, it was the prosecution of Rocco Luciano Spagnolo, an auditor from Griffith in respect of his audit work for an insurance broker in Merryjig in rural Victoria.

There was a flurry of activity in 2021 where a stupefying 9 auditor registrations were achieved, as well as 27 ‘withdrawn’ by ASIC. It may be a coincidence, but this indefatigable incursion into the world of work follows the Senate Inquiry into Audit, described here as perhaps the most useless inquiry of the modern world.

A merry jig indeed

Rocco and his client Rennie de Maria might have been caught in the cross-hairs of ASIC’s hard-hitting CADB but they had the disadvantage of being small nobodies in the world of audit, not the Big 4.

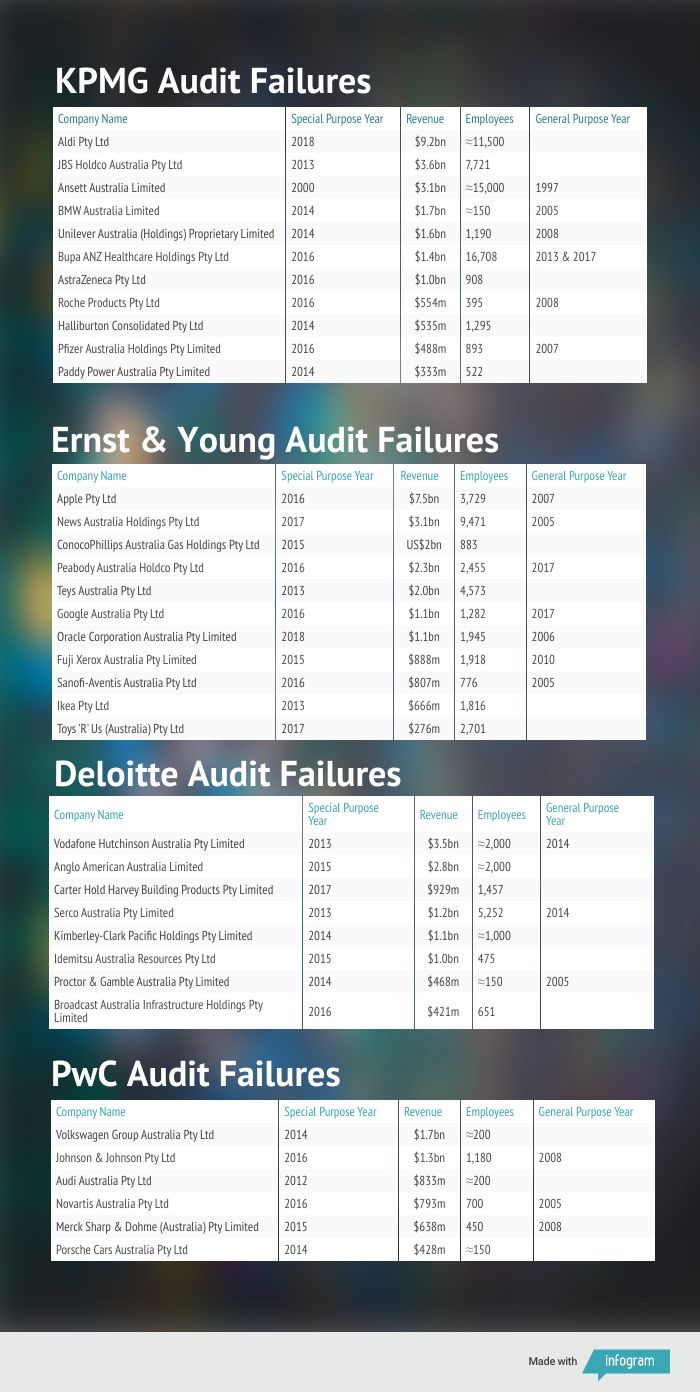

That is, not a Rupert Murdoch, not a Pfizer or a Glencore, not a Lendlease or a Goldman Sachs or American Express. Not a member or a client of the Big 4. Here is a quick “Dirty Dozen” whwere airily missed by the CADB.

Rupert Murdoch’s News Australia Holdings (News Corp)

His accounts signed off by EY, Rupert’s flagship in Australia is a master at siphoning money out of the country. His accounting wizards devised a scheme a few years ago where they cooked up a $7 billion billion soufflé of intangibles from which they helped themselves to $4.5 billion in capital returns over ensuing years, $4.5 billion tax-free ripped offshore.

That’s not all. Regarded for many years by the Tax Office as Australia’s “number one tax risk”, Rupert’s auditors also sign off on “Special Purpose” accounts, bush-league accounts which minimise disclosure to maximise tax avoidance.

By producing Special Purpose accounts, News is asking Australians to believe that – even though this company employs thousands and affects the course of government in this country – the only parties who have a stake or an interest in seeing these “public” statutory accounts are a couple of Rupert-controlled shareholders overseas.

There’s more. A few years ago we outed News for orchestrating a $903 million loan to Foxtel. As if Foxtel needed a loan at the very apogee of its profitability. No matter, the loan carried a hefty interest rate of 12 per cent. So News was effectively lending money to its cashed-up pay TV business Foxtel at 12 per cent, claiming tax deductions on the loan and lending the money back to itself at an interest rate of zero.

Goldman Sachs

The Wall Street investment bank makes hundreds of millions of dollars in income in Australia but if you shell out $41 for a copy of its “public” financial statements, the head entity in Australia, Goldman Sachs Holdings ANZ Pty Ltd, disclosed revenues of just $US24 million (2016), well shy of the $US45 million booked in finance costs.

How do they do it? They don’t bother to consolidate (to include all companies in the stable) so the accounts for the world’s most powerful investment bank in Australia are meaningless. Auditor is PwC.

SABMiller

How do you sell $3.5 billion worth of beer a year to Aussies but pay no tax? You engineer a takeover, generate billions in paper losses, and match them off against your profits for years to come. Auditor PwC.

Instead of billions in beer sales you will only find $57 million in income in SAB’s accounts because, like Goldman, the accounts are not consolidated so they simply don’t show all the earnings. Directors and auditor even have the cheek to label this brewing giant a “small proprietary company”.

William Hill

Paying millions in audit fees certainly does not ensure getting it right. Accounting academic Jeff Knapp discovered a $55 million black hole in the accounts of William Hill, Australia’s largest better company,

“They are showing a false exchange rate in the annual report,” said Knapp. “We can say with reasonable confidence that the amount shown for equity in the financial statements is out by £30 million ($55 million).

“The balance sheet has to balance. So that (the £30 million hole) means something else is wrong in the financial statements.” Auditor is Deloitte.

American Express

Amex has managed to pay no tax for a decade in Australia thanks to a suspect restructure the company did in 2004 which has siphoned out billions to an associate in the tax haven of Jersey. Auditor PwC.

Lendlease

Like Amex, Lendlease has managed to pay almost no tax in Australia for ten years. Its accounts are a supreme exercise in financial engineering which bump up profits through accounting manoeuvres such as asset revaluations and reclassifications. The upshot is to distort the responsibilities of auditors and directors because they fail to produce “true and fair” financial statements.

But the piece de resistance is that Lendlease has been buying retirement villages, claiming a bonanza of deductions by changing the contracts from lease to loan arrangements, booking the benefit of those deductions to its bottom line, and ignoring the tax law that says you can’t double dip.

It surely doesn’t help that Lendlease has had the same auditor since 1957, KPMG.

Burns Philp and Carter Holt

This one again epitomises the gaming of the rules by auditors for their multinational clients. Deloitte signed off on accounts of tricky dual holding company structure designed to bamboozle regulators and the Tax Office.

True to the form of the Big Four, Deloitte is therefore instrumental in abusing the spirit of the tax and disclosure laws, which are intended to show a true and fair picture, to help rather than to hinder.

According to Jeffrey Knapp, the retired UNSW accounting lecturer, Special Purpose financial reports for corporate groups with total income approaching $1 billion are an “abomination masquerading as transparency.”

Ansett

Perhaps the most profitable insolvency in Australian corporate history, Ansett’s managed to lose eight years of audited financial accounts. ASIC says it issued a financial reporting exemption covering the other two years of this 10-year administration (2004-05), but that document has never been made public.

The year before the airline bit the dust in 2001, Ansett produced non-compliant financial statements because they ignored the accounting standards for related parties and financial instruments.

Glencore

Formerly audited by EY (now Deloitte), the Swiss-controlled coal giant paid almost zero tax for years in Australia despite revenues of more than $5 billion a year. One trick to radically reduce its tax exposure was to take large, unnecessarily expensive loans from its associates overseas.

At the top of the China boom, Glencore’s operations here were borrowing $3.4 billion from overseas associates at an exorbitant interest rate of 9 per cent, double what the company would have had to pay had it simply borrowed the money from the bank.

In other words, EY was signing off on accounts which were to the benefit of foreign bodies corporate rather than the company it was auditing.

Apart from being one of the world’s most aggressive tax avoiders, Glencore’s accounting and its corporate structure in Australia makes it impossible to get a true picture of the group’s financial affairs. As one of this country’s biggest exporters, the cost to Australians has been immense.

Glencore is given to constant restructuring, which clouds the picture in accounting terms. When we last searched them – a painstaking and expensive process – the head entity in Australia didn’t even have a name, just a number, GHP 104 160 689 Pty Ltd.

This enigmatic entity is in turn owned by a Glencore International Investments Ltd, domiciled in Bermuda. You get the picture. It has since been restructured again.

Pfizer

Pfizer and KPMG had ample time to respond to questions before we published a story revealing a sham, a series of transactions designed to avoid tax by creating almost $1 billion in share capital. They didn’t.

In an ultra aggressive tax ploy, Pfizer “invested” almost $1 billion of cash in two companies in the Netherlands which went belly up within three years and left the Australian entity – indeed Australian taxpayers – carrying the can for its losses as the freshly created $1 billion in share capital is now sitting pretty for tax-effective distribution to Pfizer overseas.

Share capital created, assets written off. This is the Pfizer pattern. They create share capital and then the assets vanish.

Compass Resources

Here we have KPMG as the incumbent auditor of the company but it does not do the review of the Melbourne Cup half-year accounts. Rather, an auditor hand-picked by Ferrier Hodgson comes in and signs off on a set of half-year accounts that conveniently ignore 139 days that Ferrier Hodgson was in charge of the company.

ASIC’s Regulatory Guide 26 states that ”Opinion Shopping” is the practice of searching for an auditor willing to support a proposed accounting treatment. It is unlikely that a Big Four audit firm such as KPMG would associate itself with a 42-day financial report with zero comparatives.

So the Compass Melbourne Cup half-year accounts are audited by Grant Thornton. Yet – in a storyline redolent of the Twilight Zone – the auditor of the company is KPMG. The Compass Christmas Eve disclosure states that KPMG and Grant Thornton are joint auditors of the Compass Melbourne Cup half-year accounts.

The Corporations Act does not allow two firms to be jointly appointed auditor. The act refers to the appointment of ”a firm,”, one firm that is.

If KPMG and Grant Thornton were the joint auditors for these accounts, how is it that Grant Thornton alone signed the audit review report?

Aldi

This one is funny because when you open up the Aldi accounts, there are no numbers in it. The P&L, the balance sheet, the cashflow statement, all unblemished by the presence of actual numbers.

“Without transparency, there is no trust. Robust and balanced external reporting is needed” KPMG told Twitter via a conference. But its Aldi accounts don’t even show a revenue number.

Aldi actually makes about $7 billion in grocery sales, but it also has a tricky partnership structure which it relies on for minimal disclosure.

Back to the Senate

In the hearings last week, it emerged via testimony by CADB chair Maria McCrossin that there might be a “cultural problem” with the CADB. Also that the CADB had been somewhat starved of both resources and referrals from corporate regulator ASIC.

The way it works, at least in theory, is that ASIC refers cases to CADB and CADB prosecutes them. To be fair to CADB, it is just one of a coven of useless agencies, associations, regulators and peak bodies who represent or oversee the Big 4. All of them, from the Financial Reporting Council to AASB and CAANZ have been completely unaccountable when approached for comment over the years by this journal.

Maria McCrossin is pushed to answer on “the attitude” of ASIC, towards the Companies Auditors Disciplinary Board.

“Not consultative”

“I don’t think the relationship is one on a level playing field, let’s say that” #Estimates pic.twitter.com/uVsA8CdHIT— stranger (@strangerous10) November 2, 2023

They are big on making submissions to inquiries, giving the appearance of usefulness, making the right noises, but when it comes to holding multinationals and Big 4 to account … feckless. They are cowed by the might of the Big 4.

Solutions solutions

As they are so big, so pervasive and so dominant, the Big 4 ought to be broken up along tax, audit and consulting lines. The myriad audit fails are clear evidence that the global accounting firms are beyond the law. Their failure to properly carry out their role as guardians of commerce puts the entire financial system at risk.

Their role in orchestrating tax avoidance, along with the rising concentration of power and falling standards, is causing economic loss as billions are raked offshore to tax havens. Government and regulators, if they had the will, could go some way to arresting the slide by forcing proper financial disclosure.

A few years ago, accounting academic Jeff Knapp exposed the rort by the Big Four to switch their multinational clients into skimpy Special Purpose financial reporting. We revealed dozens of the world’s largest corporations operating in Australia had changed from General Purpose accounts to Special Purpose. This trend went hand in hand with more aggressive multinational tax avoidance.

As Jeff Knapp puts it: “The Big Four auditors have knifed general purpose financial reports for multinationals and taken Australian accounting practice back 30 years”.

Michael West established Michael West Media in 2016 to focus on journalism of high public interest, particularly the rising power of corporations over democracy. West was formerly a journalist and editor with Fairfax newspapers, a columnist for News Corp and even, once, a stockbroker.